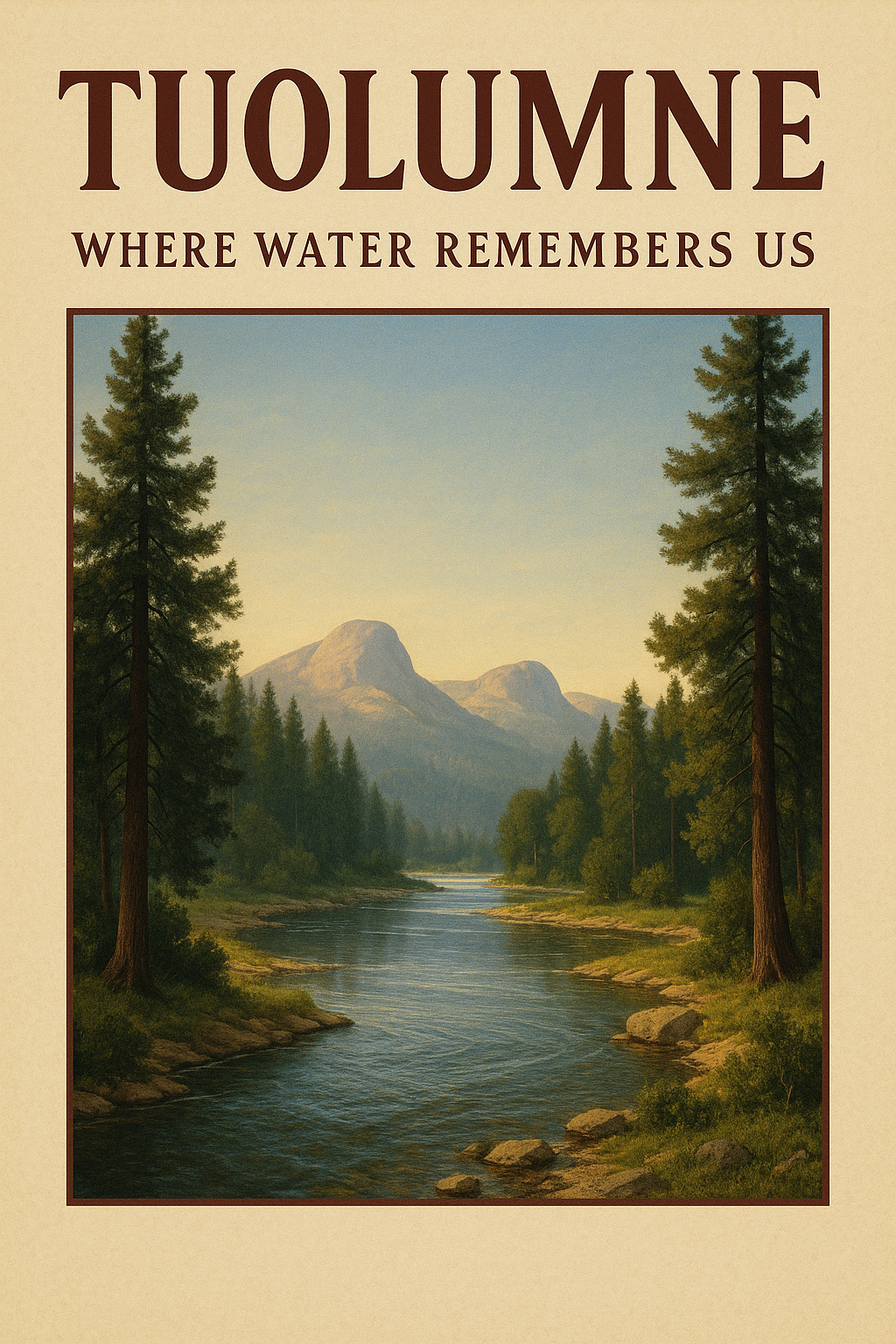

A Story About Water, Fathers, and Ceremony

Water doesn’t forget. It holds memory in its flow, carries the weight of things left unsaid, and reflects the stories that ripple through bloodlines. In Deborah A. Miranda’s haunting and healing narrative, Tuolumne, a river becomes the place where a broken bond begins to mend—and where a family finds a sacred path forward. As I read her memoir, I felt the current of something familiar, something deeply rooted in the longing to be seen, to start over, to be held by something bigger than pain.

Miranda writes about a pivotal, almost wordless encounter between her father, Al—newly released from incarceration—and his father, Tom. The visit is unannounced, unexpected. Years of distance, emotional neglect, and cultural disconnection loom large between them. And yet, instead of pushing him away, Tom takes his son to the river.

“In that moment, even if he could not articulate why, the river was the one thing Tom could offer to a son in need of a ceremony to begin his life over” (Miranda 67).

This moment doesn’t rely on conversation. It doesn’t wrap itself in apology or explanations. The gesture is enough. The river becomes a bridge—between father and son, past and future, trauma and healing.

Years later, when Al is dying, he asks that his ashes be scattered at the same river. It’s a request heavy with meaning. The river that marked his new beginning is the one he chooses for his return to the earth. For his children, the river becomes sacred. They now return to it when they are hurting, seeking, grieving, or needing to start again.

Observations on the Writer, Genre, and Audience

Deborah A. Miranda is a poet, memoirist, and Indigenous voice whose work often examines identity, history, and survival. In Tuolumne, her writing is spare and lyrical, steeped in cultural meaning and emotional depth. You can feel how much is being held in restraint—how much pain and love are layered into every sentence.

The genre is memoir, but it acts as both personal narrative and cultural testimony. It is the story of her father’s partial redemption, her family’s connection to place, and the quiet legacy of Indigenous ceremony.

The intended audience seems to be anyone who has lived through emotional estrangement, particularly between parent and child. But more broadly, it speaks to those whose familial history is marked by erasure, incarceration, or cultural disconnection—experiences familiar to many Indigenous families and communities of color.

“The River Was the One Thing…”

That one quote lingers like the hum of water after the rain:

“The river was the one thing Tom could offer…” (Miranda 67).

In this simple line, Miranda captures the essence of inheritance—not of land, or money, or words, but of place. Of ceremony. Tom likely didn’t know how to express fatherhood in the way Al needed it, but he knew the river. He trusted the water to speak for him. That was the offering. That was the gift.

The Natural World as Healer

The story of Tuolumne illustrates something I’ve long believed: nature is more than a backdrop—it is a participant in our healing. For Al, that river marked the beginning of a shift in his life. Though we don’t know the full trajectory of his path, we know that moment changed something.

When people have been traumatized—by incarceration, by generational neglect, by cultural loss—words often fail. But nature doesn’t. Rivers, forests, mountains—they offer us presence without judgment, movement without pressure, stillness without expectation.

The river in Tuolumne is more than a body of water—it becomes a ceremony. A rite of passage. A place of return.

And this isn’t unique to Miranda’s story. Across cultures, rivers have long been spaces of rebirth:

- In Christianity, baptism in water symbolizes new life.

- In Yoruba spirituality, the river deity Oshun represents healing, love, and fertility.

- In Indigenous traditions across North America, rivers are often considered living relatives.

Healing through nature is not metaphorical—it’s ancestral. It’s encoded in the stories we carry and in the rituals we return to when language isn’t enough.

A Legacy Carried in Water

After Al’s death, Miranda and her siblings bring his ashes to the river. They continue to visit, not just as a site of mourning, but as a place of cleansing, guidance, and spiritual reconnection.

This story reminds me that healing is rarely a single act—it’s cyclical. The river carries not only Al’s memory, but the legacy of a father who tried, in his own silent way, to give his son something sacred. That one act—however imperfect—rippled outward, reaching the next generation.

Miranda writes with reverence, not only for her family but for the land that holds their stories. And as I reflect on my own life, I realize how often we search for rivers—real or symbolic—to cleanse ourselves of the past and find the strength to begin again.

Final Reflection from Poetic Bipolar Mind

At Poetic Bipolar Mind, I write through grief, healing, trauma, and love. Miranda’s Tuolumne fits right into that emotional landscape. It reminds me that while our wounds may be inherited, so can our ceremonies. We carry pain, yes—but we can also carry sacred places, rituals, and symbols that help us begin again.

For anyone navigating broken family bonds, cultural fragmentation, or the ache of needing something that was never given, Tuolumne is a soft place to land. It doesn’t give easy answers. But it gives the river.

And maybe that’s enough.

Works Cited

Miranda, Deborah A. “Tuolumne.” The Human Tradition in California, edited by Clark Davis and David Igler, Rowman & Littlefield, 2017, pp. 64–67.

Leave a Reply