Wrestling with Dylan Thomas’s Defiance of Death

Dylan Thomas’s villanelle Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night has become one of the most famous meditations on mortality in modern poetry. Written as his father neared death, the poem does not soothe with resignation. Instead, it burns with defiance:

“Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight /

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, /

Rage, rage against the dying of the light” (Thomas 1182).

Thomas presents his father—and all of humanity—with a command: resist death. Do not surrender to its shadow, no matter age, weakness, or circumstance.

The Paradox of “Blinding Sight”

One of the most striking phrases in the poem, “blinding sight,” embodies an oxymoron. To see with clarity and to be blinded are contradictory states, yet Thomas fuses them. These “grave men,” seasoned by life, approach death with a kind of paradoxical vision—an awareness sharpened by proximity to the end, yet obscured by its inevitability. Their eyes, though failing, “blaze like meteors,” radiating brilliance in the very moment they dim.

The imagery suggests that the closer we come to death, the more urgently life asserts itself, even if in flashes. For Thomas, mortality is not a quiet surrender but a spark that illuminates the meaning of existence.

Fighting Death vs. Accepting It

Yet the poem raises an ethical and emotional question: is it fair to demand that the dying resist? Thomas urges his father to “rage, rage against the dying of the light,” but he never shared this poem with him. Perhaps he recognized the selfishness in pressing a man on his deathbed to resist when what he might need most is peace.

This tension is one I feel deeply. To me, the idea of battling death seems futile. If it is my time, I would rather meet it calmly, without fear, without defiance. Acceptance is not weakness—it is courage in its own right. While Thomas’s poem insists on resistance, I cannot help but believe that peace is another form of strength.

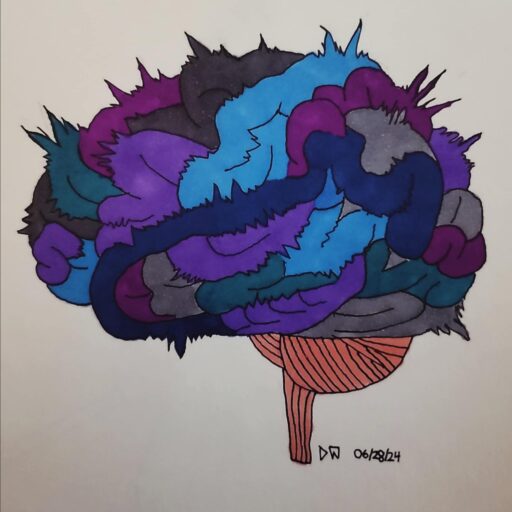

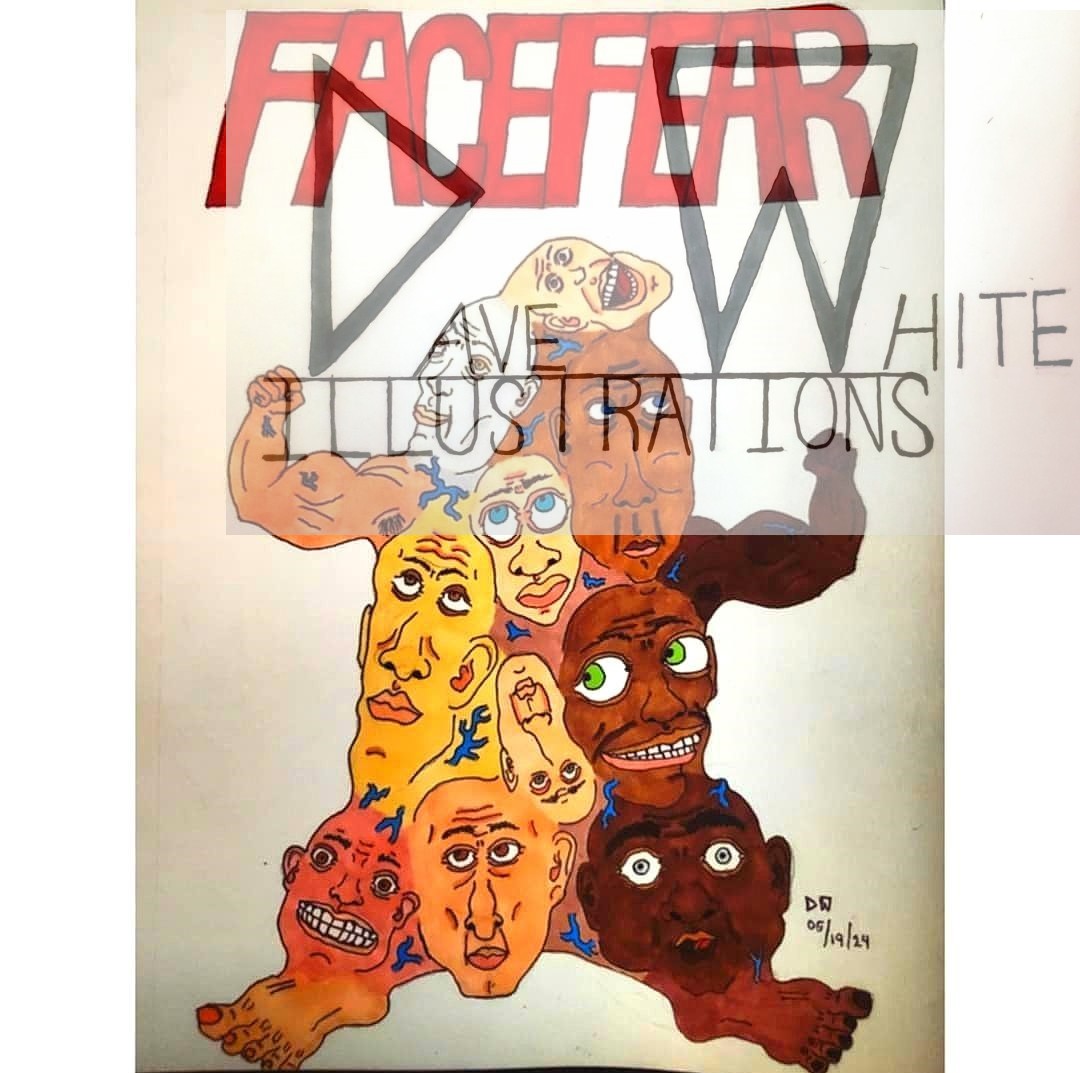

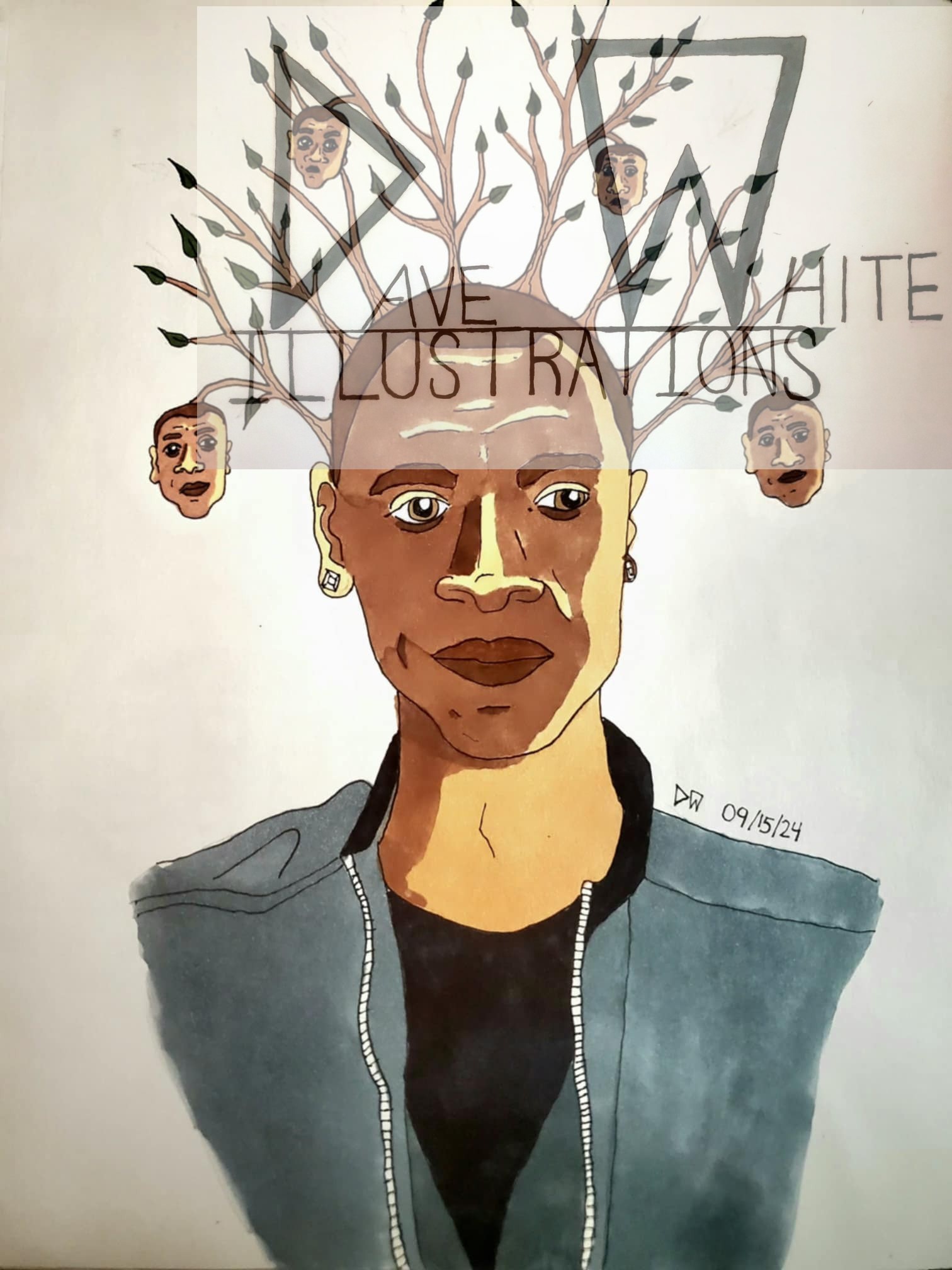

Poetic Bipolar Mind and the Dance with Mortality

On Poetic Bipolar Mind, I often write from that fragile line between rage and acceptance. Like Thomas, I have felt the lure of defiance—fighting against despair, addiction, grief, and the pull of self-destruction. But I have also found moments where surrender, not as defeat but as release, allowed me to heal.

PBM is my own “blinding sight”: a paradoxical place where brokenness reveals clarity, where suffering blazes into testimony. The poems and essays I publish are my way of refusing silence. Sometimes they rage; sometimes they accept. But all of them honor the truth that living is a dialogue with death—one that must be written, spoken, and shared.

Works Cited

Thomas, Dylan. “Do not go gentle into that good night.” Exploring Literature. Pearson, Boston, p. 1182.

Leave a Reply