Greek Philosophy’s Eternal Echo in the Human Soul

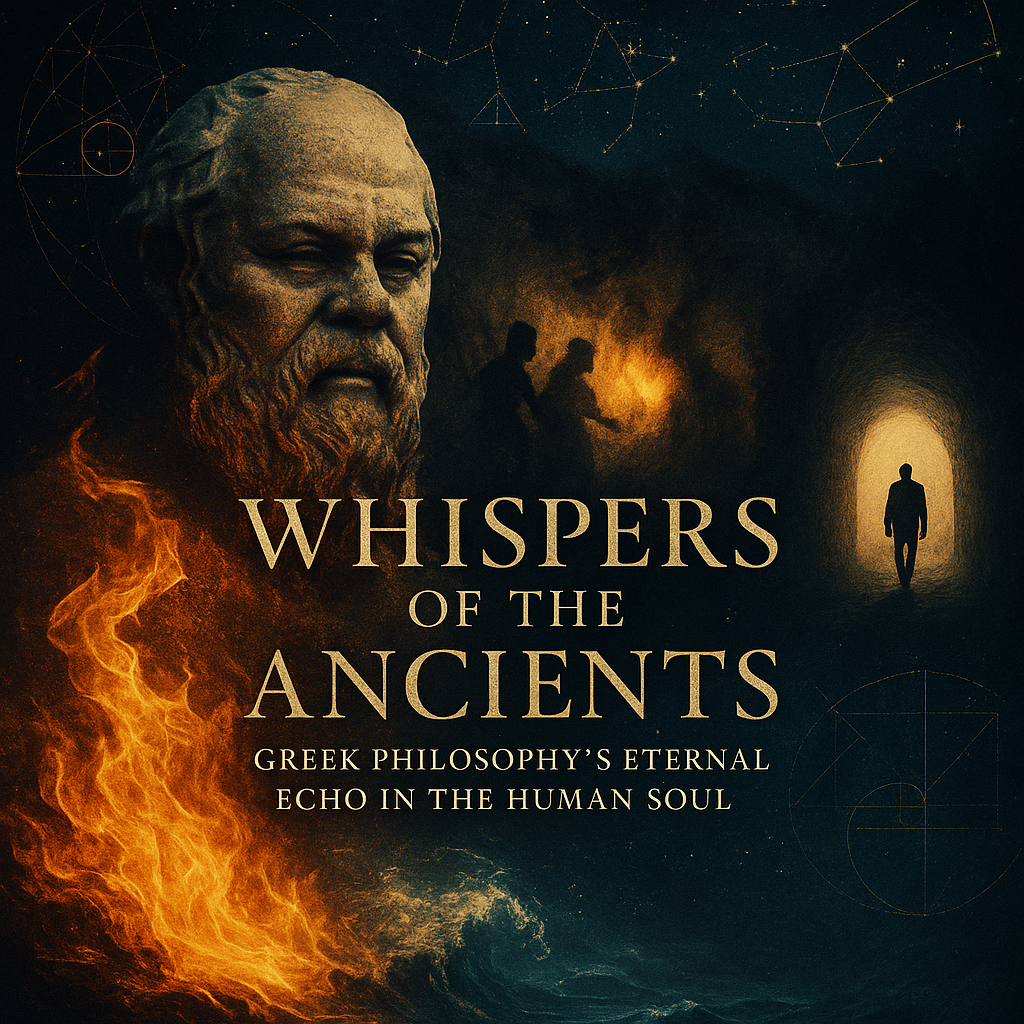

When we look back at the ancient world, it’s easy to imagine philosophy as something abstract, reserved for marble halls and ink-stained scrolls. Yet Greek philosophy was never just about theories—it was about how to live, how to suffer, and how to rise. It was born from myth, tested by logic, and tempered by human longing.

Before philosophers walked the earth, poets sang. Homer and Hesiod tried to explain the universe through myth: gods warring, lovers mourning, the cosmos unfolding in story. These myths weren’t mere entertainment—they were maps for how to live, warning us of hubris, teaching us courage, whispering of the sacred in the mundane. Myths sought to explain the unfamiliar in the language of the familiar.

But then came Thales of Miletus, who dared to ask: what if the world could be understood not just through story but through reason? He looked to water—the flowing, changing, life-giving element—as the root of all things. In his question, “Why a universe and not a multiverse?” lies a timeless echo: our need to understand why anything exists at all.

Thales began the lineage of thinkers who shaped the foundations of Western thought: Anaximander, with his infinite Apeiron—the boundless, the undefined, the primordial womb of existence. Anaximenes, grounding life in air, the breath that sustains us. Pythagoras, who heard harmony in numbers and believed that purification of the soul could free us from the wheel of birth. Heraclitus, the firebrand who declared, “This world-order, the same for all, none of the gods nor of men has made … an ever-living fire.”

Each of these voices carried a paradox: permanence and change, chaos and order, the seen and the unseen. They were not only shaping metaphysics but also the human psyche. Heraclitus urged us to embrace paradox: that conflict itself is the seed of justice. Parmenides demanded we trust reason even when it defied our senses. Socrates reminded us that “the unexamined life is not worth living.”

These ancient minds were not distant—they are mirrors. When I read Xenophanes’ rejection of gods shaped in the image of man, I hear my own rebellion against the narratives handed down to me—stories I had to question in order to find truth. When I reflect on Plato’s allegory of the cave, I see shadows I’ve mistaken for reality, and I remember the painful light of awakening. When Aristotle insists that happiness is the final cause, the true telos of our existence, I recognize the same hunger for meaning that drives me to write.

Greek philosophy’s lasting legacy is not only in shaping politics, science, or theology—it is in reminding us that human beings have always sought to reconcile suffering with wisdom, fear with knowledge, and mortality with transcendence.

For Poetic Bipolar Mind, these echoes matter. They remind me that my struggles with grief, identity, and silence are part of a continuum of questioning. The philosophers spoke of the soul, of purification, of justice born from conflict. My soul, too, seeks purification in the act of writing. My conflicts, too, are paradoxes that generate growth.

Philosophy, like poetry, is not about answers. It is about daring to ask the hardest questions—and being willing to sit in the space where answers never fully come. The ancients knew this. Their words, carried across centuries, are reminders that even in darkness, reason and wonder can walk together.

We inherit their questions as much as their answers. And perhaps that is the greatest gift of Greek philosophy: to remind us that being human is to be both lost and searching, fragile and fierce, mortal yet dreaming of immortality.

Works Cited

Adler, Mortimer Jerome, and ADLER. Aristotle for Everybody: Difficult Thought Made Easy. New York, Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, 1997.

Connole, Joseph. “Plato and Aristotle’s Regimes: Republic and Politics.” Formatia Trans Sicere Educatorum, Federalist Publicola, 15 Oct. 2007.

Heraclitus. Fragment 30. In The Presocratic Philosophers, edited by G.S. Kirk, J.E. Raven, and M. Schofield. Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Lawhead, William F. The Ancient Voyage: The Greeks and Romans. 2nd ed., Wadsworth Publishing, 2001.

Linder, Doug. “The Trial of Socrates: An Account.” Famous Trials Project, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/socrates/socratesaccount.html. Accessed 22 Feb. 2017.

Merriam-Webster. “Knowledge.” 2016. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/knowledge. Accessed 12 Dec. 2016.

Vanier, Jean. Made for Happiness: Discovering the Meaning of Life with Aristotle. House of Anasi Press, 2012.

Zachary, Gilbert. “Aristotle 384 – 322 BC.” Philosophy 101. SUNY Westchester Community College, New York. Nov. 2016.

Zachary, Gilbert. “Socrates vs The Sophists and The Citizens of Athens (The Death Knell of the Athenian Republic).” Philosophy 101. SUNY Westchester Community College, New York. Oct. 2016.

Leave a Reply