Your cart is currently empty!

Condemned to Choose

Sartre, Faith, and the Beautiful Burden of Free Will

What does it mean to be free?

Philosophers have wrestled with this question for centuries, pulling it apart like a knot that tightens each time one tries to loosen it. Free will, at its most basic, is the ability to make choices unshackled by outside force. Yet when we look closer, we discover that freedom is never as simple—or as limitless—as it sounds.

For some, free will is inseparable from moral responsibility: if we are free, then the weight of every choice presses down upon us. If we are not, then accountability dissolves into excuse. But what if the truth lies in a restless middle ground?

Sartre’s Vision: Freedom Without Escape

The French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre offered one of the most radical interpretations of freedom. He declared that existence precedes essence: we are not born with a prewritten purpose, nor are we carved from divine design. Instead, we arrive in the world blank, only to define ourselves through the choices we make.

“If existence really does precede essence, there is no explaining things away by reference to a fixed human nature. In other words, there is no determinism, man is free, man is freedom” (Existentialism Is a Humanism).

In Sartre’s philosophy, all things fall into two categories:

- Being-in-itself: unconscious objects, fixed in their use and purpose—a rock can only be a rock.

- Being-for-itself: conscious beings, capable of self-reflection, responsibility, and freedom—humans, who must define their own existence.

From this distinction, Sartre delivers his most haunting proclamation:

“Man is condemned to be free… he carries the weight of the whole world on his shoulders” (Being and Nothingness, p. 350).

We are condemned, because we did not choose to be born. Yet once alive, we can never escape choice. Even refusing to choose is still a choice, and each one chains us to its consequences. There is no hiding, not even behind God, whom Sartre considered a human invention to soften the sting of responsibility.

The Weight of Nature and the Voice of Faith

But Sartre’s freedom is unsettling precisely because it feels too absolute. Reality shows us the edges of choice. We are free to dream, but not free to transcend the boundaries of nature.

Imagine a woman who longs for the Bahamas. She may choose to board a plane, or she may stay home. But she cannot teleport there, no matter how fierce her desire. Her will is powerful, but not infinite.

Scripture echoes this paradox, reminding us that humanity bears choice but not ultimate sovereignty:

- “He works all things according to the counsel of his will” (Ephesians 1:11).

- “Our God is in the heavens; he does all that he pleases” (Psalm 115:3).

- “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23).

Here, only God is truly free. Man, by contrast, is hemmed in by sin, nature, and the limits of flesh. We can choose, but never outside the framework of our human condition.

This is why freedom often feels less like liberation and more like burden. Jesus declared, “You refuse to come to me to have life” (John 5:40). The people had the power to choose, but their refusal sealed their fate. As Paul later warns, “A man reaps what he sows” (Galatians 6:7).

Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor, in The Brothers Karamazov, voices the agony of this paradox: “Why has Jesus bound the intolerable burden of absolute freedom on poor, feeble, depraved humanity?” Freedom, unguarded, can seduce the soul into ruin.

The Double-Edged Gift

Freedom is intoxicating: it is the shimmer of possibility, the chance to shape one’s life. Yet it is also terrifying: the knowledge that every decision bears consequence, that every path not taken lingers as ghost.

Sartre is right to tether freedom to responsibility—our choices are ours alone. But to say that freedom is without limit is to overlook the gravity of nature, body, and spirit. Freedom is real, yes, but it is not infinite. It is a double-edged gift, equal parts light and burden.

The Human Echo

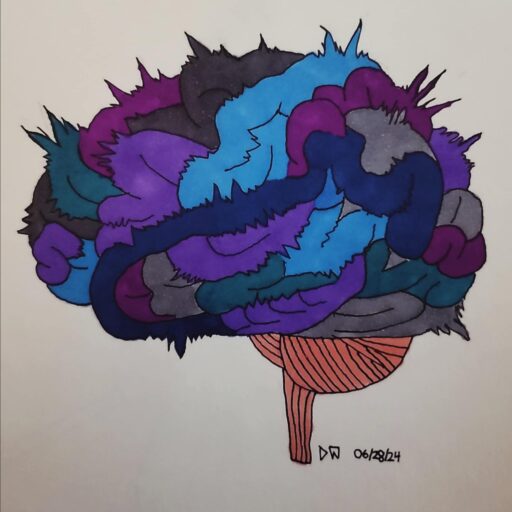

This paradox is not just a debate between philosophers and theologians. It is a mirror of our lived lives. To be free is to walk the line between desire and restraint, to feel the thrill of possibility and the ache of limitation.

In the inner storms of the human mind, this burden is deeply felt. Freedom can both empower and torment. It can inspire us to rise, or leave us drowning in the consequences of our choices. It is a haunting rhythm, echoing through every soul: the ache of choice, the terror of responsibility, the longing for grace.

This echo—freedom as both salvation and sorrow—is what makes the question of free will not only philosophical, but profoundly human.

Works Cited

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990.

- Holy Bible, English Standard Version. Crossway Bibles, 2001.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. Being and Nothingness. Translated by Hazel E. Barnes, Washington Square Press, 1992.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. Existentialism Is a Humanism. Translated by Carol Macomber, Yale University Press, 2007.

Discover more from Poetic Bipolar Mind

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

-

Eternal Expressions

Hieroglyphics and statues were not mere artifacts—they were Egypt’s testimony against time. From rigid depictions of divine order to individualized portraits of wisdom, these forms carried memory and spirit. On Poetic Bipolar Mind, I see writing as a similar practice: a modern hieroglyph, preserving lived experience against silence and forgetting.

-

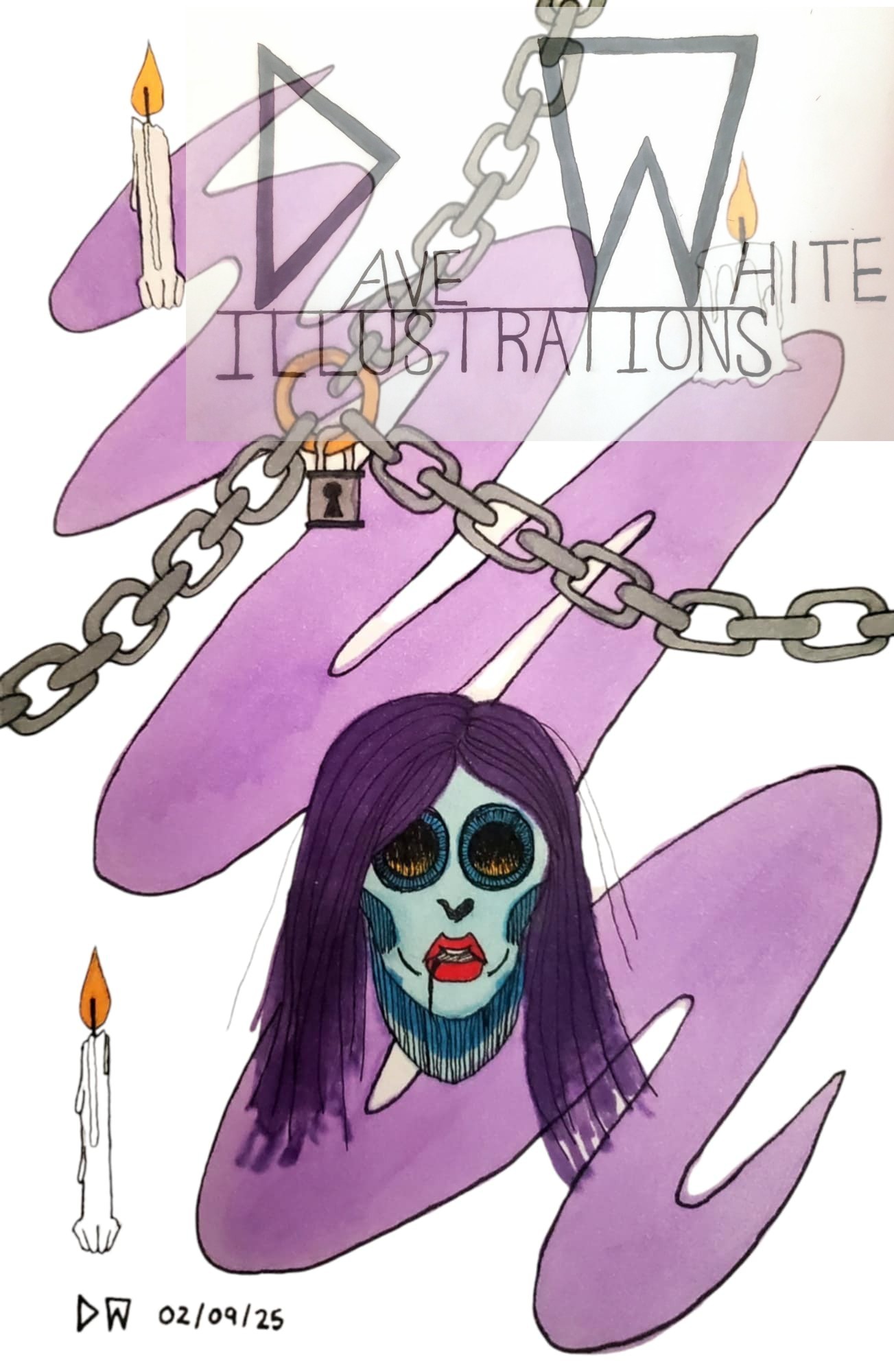

Bound by Time and Memory

Dave White’s Forgotten Soul and Kiana Jimenez’s poem intertwine in a meditation on eternal love, memory, and entrapment. Chains, locks, and flickering candles mirror verses of clocks and longing, creating a haunting narrative of two damned souls bound together beyond time’s reach, refusing to fade even as shadows close in.

-

Damned Souls

Damned Souls captures love as both solace and torment, where time itself becomes the pulse of longing. Through haunting rhythms and tender imagery, the poem binds two souls in passion, darkness, and eternal memory—a love story etched in stars, shadows, and the unyielding tick of the clock.

Leave a Reply