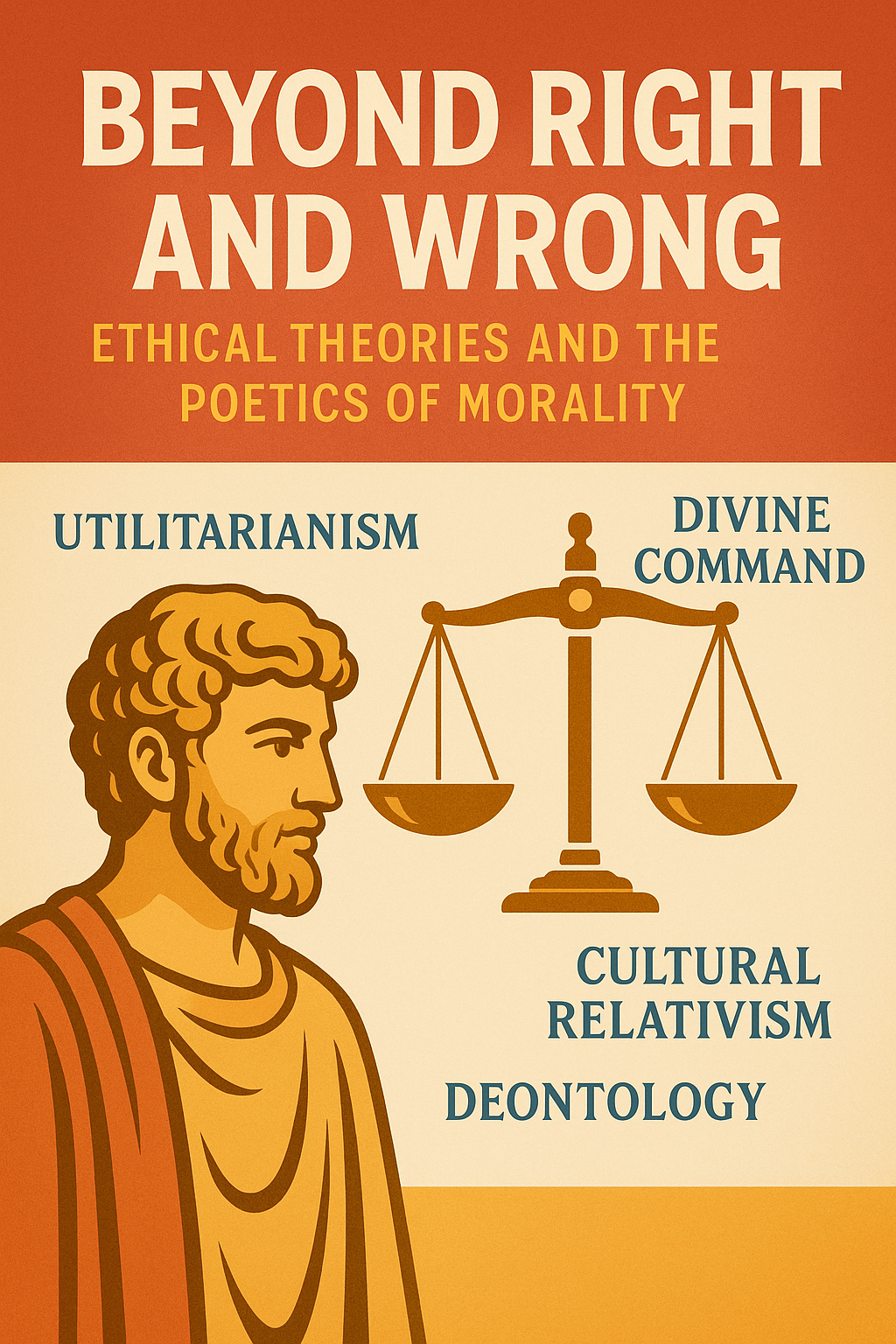

Ethical Theories, Human Choices, and the Poetics of Morality

Introduction: The Question That Won’t Go Away

What does it mean to be good? To live well? To make the right choice when everything feels impossibly complicated?

Philosophers have wrestled with these questions for centuries, and in our modern age—shaped by technology, global crises, and rapidly shifting cultures—ethical reflection feels more urgent than ever.

Ethics, at its core, explores the principles of right and wrong, guiding human beings toward a vision of the good life. Yet ethical theories often collide—sometimes dramatically—over whether morality is universal, subjective, culturally constructed, or divinely ordained.

As Aristotle once wrote in Nicomachean Ethics:

“The good for man is an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue.”

But what counts as virtue? Who decides? And what happens when personal morality and collective norms disagree?

Ethical Theories: Mapping the Moral Landscape

Ethical philosophy branches into multiple perspectives—some rooted in universal principles, others in cultural norms, divine authority, rational self-interest, or human emotion. Let’s explore a few central frameworks, with real-world examples to ground them.

1. Ethical Subjectivism

Ethical subjectivism claims that morality depends on individual feeling rather than collective standards or divine commands. Moral truth, for the subjectivist, lives within the self.

- Example: A 20th-century Dominican citizen under Rafael Trujillo might have viewed his authoritarian rule as acceptable or even necessary, despite its brutality, because personal or cultural loyalty outweighed abstract moral critique.

As philosopher James Rachels notes in The Elements of Moral Philosophy:

“Subjectivism teaches that moral opinions are not true or false; they are only expressions of attitudes.”

2. Cultural Relativism

In contrast, cultural relativism locates morality within societies rather than individuals. Different cultures develop different moral codes based on survival needs, traditions, and worldviews.

- Example: Practices like arranged marriage or dietary laws often reflect deeply embedded cultural ethics that outsiders might misunderstand or condemn.

This theory insists on empathy and cultural humility, though critics argue it risks excusing harmful traditions under the banner of “respect.”

3. Divine Command Theory

Here, morality depends entirely on God’s will. Actions are right because God commands them, wrong because God forbids them.

- Example: The Ten Commandments in Judeo-Christian tradition illustrate this moral framework: “Thou shalt not kill” requires no justification beyond divine authority.

Yet philosophers like Plato, in Euthyphro, raised a critical question:

“Is the good loved by the gods because it is good, or is it good because it is loved by the gods?”

4. Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism measures morality by outcomes. The right action produces “the greatest happiness for the greatest number,” as Jeremy Bentham argued.

- Example: Modern public health policies often reflect utilitarian reasoning, balancing individual freedoms against the well-being of entire populations.

5. Deontology

Immanuel Kant’s deontological ethics grounds morality in duty, rules, and universal principles rather than consequences. Right action, for Kant, stems from rational obligation:

“Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.” (Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals)

For deontologists, lying remains wrong even if it produces good results, because morality transcends outcomes.

6. Ethical Egoism

Ethical egoism centers morality on rational self-interest. Critics see selfishness; defenders argue for personal responsibility and long-term flourishing.

- Example: A career choice prioritizing personal happiness over family expectations may reflect egoistic ethics—controversial, yet defensible within this framework.

7. Natural Law Theory

Natural law theorists, from Cicero to Thomas Aquinas, claim morality arises from human nature and reason itself. Life, knowledge, procreation, and community represent universal goods embedded in the human condition.

8. Emotivism & Noncognitivism

For emotivists, moral claims express emotions rather than objective truths. Saying “Stealing is wrong” translates roughly as “Boo to stealing!”—a cheer or jeer, not a factual statement.

This view unsettles those seeking moral certainty yet captures how people often use morality to persuade rather than to prove.

Tying It to Poetic Bipolar Mind

Why discuss ethics on a platform blending poetry, mental health, and art? Because Poetic Bipolar Mind inhabits the same terrain where philosophy meets lived experience.

- When we write about grief, we echo existential ethics, confronting suffering without easy answers.

- When we challenge stigma around mental illness, we embody justice ethics, demanding dignity for all.

- When we share personal narratives, we reflect ethical subjectivism—truth filtered through individual experience yet resonating universally.

As poet Audre Lorde wrote:

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Ethics asks: What tools will?

Leave a Reply